MENU

DISCOVER NOW

.jpg)

ARTICLES

Glass art reflects well-being

Collecting glass art is often perceived as a niche hobby mastered for a select few. In reality, acquiring handcrafted glass is easier—and more meaningful—than many people think. It’s a personal choice that brings joy to life while supporting the vitality of culture and craftsmanship.

COURSES

Summer 2026 intensive courses announced

Registration for next summer’s glassblowing courses is now open! On the week-long intensive courses, experienced glassmakers from around the world will challenge you to push the boundaries of creativity and technique. The Early Bird offer is valid until the end of February 2026.

EXHIBITIONS

Shared Glow

PRYKÄRI VINTTIGALLERIA | 22 NOV 2025 – SPRING 2026

The exhibition brings together art works by international artists who have worked in Nuutajärvi, many of which were created in collaboration with local artisans. The pieces come from the village, the artists, and various collections.

Forest glass for the nation

In 1793, Major Jacob Wilhelm Depont pondered what to do with the vast forestlands he inherited with the Nuutajärvi estate. There was plenty of timber, but no routes to transport it.

Glass furnaces glowing at a thousand degrees devour wood—and lots of it. Depont knew this well; his father had managed the Åvik glassworks. He also knew that Sweden, the mother country, faced a shortage of window panes and that its timber reserves were tied up in iron production. So, a glass factory was founded in Nuutajärvi to produce window glass.

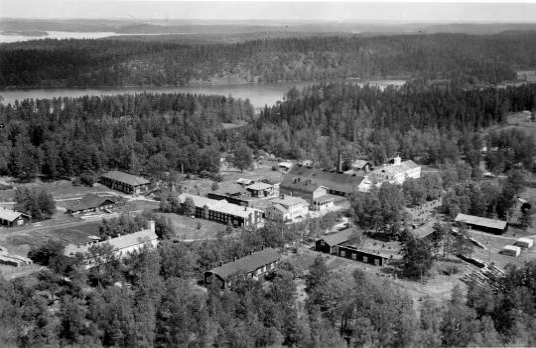

The first Nuutajärvi glass was greenish and bubbly—known as “forest glass.” The name came from its woodland origins and the green hue caused by impurities in the sand, especially iron oxide. Photo: Nuutajärvi in 1936.

STORY OF GLASS

TEXT: VIESTINTÄTOIMISTO JOKIRANTA

International flair and style

By the mid-1800s, new faces and foreign languages arrived in Nuutajärvi. Adolf Törngren, the factory’s new owner, sought knowledge and skilled workers from Central Europe. The village grew into an international hub with shops and breweries. Architect G. T. Chiewitz designed ornate Swiss and Neo-Renaissance-style buildings that still define the glass village today.

Glass evolved beyond mere utility into a showcase of style and craftsmanship—a good thing, because Nuutajärvi would never have survived as just a window glass producer.

Alongside social life, glass design and production methods advanced. Pressed glass enabled mass production, while striped filigree glass brought new vibrancy to objects. (Source: Finna)

A golden age born from ashes

In 1950, flames swept through Nuutajärvi, and the fire destroyed production facilities. The manor era ended when Wärtsilä Corporation purchased the factory. Wärtsilä already owned Arabia porcelain, giving Nuutajärvi access to commercial expertise and international sales networks.

The 1950s marked the start of Finnish design’s golden age as art glass gained recognition at international exhibitions and Milan Triennales. Consumers also voiced criticism: why not design functional everyday items?

The fire meant not an end but a new beginning for Nuutajärvi, as Wärtsilä brought in new designers. Glass advertisement from 1953.

Global fame for everyday beauty

To kick off the golden age, Kaj Franck—already a celebrated designer—was appointed artistic director. Soon, Saara Hopea joined as a designer. Both favored understated elegance: objects should be functional, durable, and beautiful.

Nuutajärvi’s practical aesthetics earned acclaim in international competitions and in everyday life. The factory focused on high-quality utility glass design, and by 1956, Nuutajärvi accounted for 70% of Finland’s glass exports.

.jpg)

Saara Hopea’s stackable tumblers softened the transition to a new, minimalist design language with vibrant color. (Source: Finna)

The colorful, experimental sixties

In the 1960s, Kaj Franck shifted production alongside Nuutajärvi’s new designer, Oiva Toikka. Glass began to play in new ways. Colors had been abundant since the early ’50s, but now combinations surprised. Filigree techniques were revived, and Franck developed a new striped color technique.

Bold hues, uneven textures, and experimental forms answered consumers’ post-war craving for abundance. By the decade’s end, Finnish glass was booming.

In the 1960s, Nuutajärvi doubled down on pressed glass expertise as new markets opened and price competition intensified. Oiva Toikka’s Kastehelmi pattern emerged as the factory sought beautiful ways to hide mold seams in pressed glass.

Birds take flight

Oiva Toikka is one of Finland’s most famous glass artists. His playful, life-affirming personality shines through in his diverse creations: monsters, candy sticks, and annual cubes. Yet Toikka was far from impractical—witness designs like Kastehelmi, Flora, and Pioni.

Toikka is best known for his hundreds of glass bird species, whose permanent home, Lintukoto, was established in Nuutajärvi in 2024. His legacy continues through the glass school he helped create.

%20(1).jpg)

Some of Oiva Toikka’s glass birds draw inspiration from nature; others spring from the imagination of a designer known for his distinctive style.

Beloved collections amid market turbulence

From the 1970s onward, markets shifted. Cheap imported glass dominated everyday use, but Finnish glass held its place on festive tables, and collectible series grew in popularity. The importance of glassblowers’ free experimentation for technical and production development was recognized. Glassmaking began to captivate the public—factories became tourist attractions.

Nuutajärvi glass was also sold under Arabia and Pro Arte brands until production moved under Iittala in 1988. Beloved series continued, even as labels changed.

Kerttu Nurminen’s Mondo glass was a bestseller showcasing Nuutajärvi craftsmanship.

The end of the industrial era

Iittala closed the Nuutajärvi glass factory in 2014, consolidating production in Iittala. The village fell silent as many glassblowers and their families moved away for work.

Glass heritage was kept alive by the glass school, a newly founded foundation, and independent artists. A new era emphasized the value of handmade glass and cultural heritage. Yet the village’s buildings continued to deteriorate, and some protected structures were condemned. It seemed Nuutajärvi’s 200-year glassmaking tradition might soon end.

.jpg)

In 2023, the knowledge, skill, and techniques of handmade glass were inscribed on UNESCO’s list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

– Olemme kumpikin vahvasti tuntevia ihmisiä, joille Nuutajärven lasiperinteen jatkuminen on sydämen asia, Teija Koskinen kertoo.

A new era for handmade glass

In 2021, the glass village’s buildings found a new owner—millions invested in the historic setting now safeguard Nuutajärvi’s glassmaking tradition. Nuutajärvi Glass is a center for handmade glass, where heritage lives and is passed on. The village’s art galleries, workshops, museums, and exhibitions invite visitors to experience the magic of glass.

Read more about the future of Nuutajärvi Glass:

Finnish at glass art deserves bold plans

Jaa tämä artikkeli:

%20(1).jpg)

DIVE INTO

THE WORLD

OF GLASS

Published once a month, the Nuutajärvi Glass newsletter showcases glassmakers, their perspectives, and current news.